Photography & Installation

From the Craftsman’s Tool to the Work of Art and Back Again – The Role of Photography in the Contemporary Installation. *

Marta Raczek, “Biuletyn Fotograficzny”, Poland, March 2004

Since its birth in the 1830’s, photography has tried to find its way into the art world. Photography’s beginning was humble, first being perceived as a useful tool for artists lacking the funds to secure live subject models and as an aid in realistically detailed landscape painting. Its first major acceptance as a independent art form in itself came with the beginning of the impressionist era at the end of the 1800’s. Artists recognized photography’s very specific features and desired to include them in their paintings. These features include a fragmentary mode of framing, vastly different from the tradition of fixed, closed-compositional painting previously established by artists. The distinct contrasting of light exhibited in early photographic works also inspired the impressionists, giving their works extraordinary new form. Nevertheless, photography was still mainly perceived as a medium most appreciated for its ability to realistically capture the world, that is, until its liberation by the birth of cinema in 1895. Having the enormous advantage of the moving image, cinema took photography’s place as the most realistic mirror of reality. The appearance of reality became the most important topic of discussion accompanied by surveys into the features of photography. The next groundbreaking moment came though the experimentation of such acclaimed artists as Man Ray and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. The annihilation of photography’s most essential aspects (Man Rays’ filmless experimentations directly on the enlarger along with Laszlo Moholy-Nagys’ projections directly on walls) and creation of abstract compostions broke with photography’s fixation on realism and signified a departure from established norms. Photography’s struggle to find its place in the art world ended in the 1950’s with its inclusion into the world’s largest art collections. From this time, experimental photography as well as more traditional styles, (no one longer perceived that photography was the perfect reflection of reality) achieved new status as legitimate art, entering the art market and very often attaining enormous head-tuning prices (for example the photographs by Japanese artist Nobuyoshi Araki).

Suddenly, at the end of the 20th century and with the beginning of the 21st,the situation has completely changed.

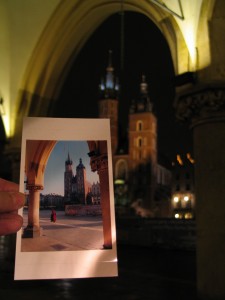

Photography has returned to the role of tool as part of the creative process, lacking its own artistic value. We can observe this shift, in Krakow’s Bunkier Sztuki, with the newest project of British artist Chris Meigh-Andrews. His work entitled “View of the Wawel Castle from Debnicki Bridge (after Ignacy Krieger)” is a free variation on Kreigers’ late 19th century work that captured this symbol of Polish history. Chris Meigh-Andrews is interested in discovering Kreiger’s perception of Krakow and in what context the buildings had existed for him. In this way, the main concern of this British artist for many years has been the connection between past and present, questions of memory and, as pointed out by the artist himself, the problem of constructing places by individuals during the process of taking pictures. In his installation the photography ceases to have a purpose of its own. The numerous photographs of the Kings’ residence are elements of a larger entity. Thanks to digital editing, video, and the adding of real, recorded sounds from the bridge, the photographs used for this installation are both still and moving. The viewer relates to the sequence of digitally recorded images permeating each other, appearing to emerge and collapse. What draws the viewers’ attention is a bird appearing to fly through the picture. So the bird becomes not only a sign of coexistence within one artwork spanning two different mediums (basically two different ways of recording the image through digital and analogue means—the 19th century photograph and the digital pictures) but also the symbol of the temporal connection between past and present (the bird recorded today is being written into the photography from the past).

Let’s return for a moment to the subservient role of photography. This medium, like the pieces recorded by the camera, loses its autonomy but gains a new dimension. They become the tools of critical analysis. This is the process in that is essential to the new role of photography. Thanks to the numerous theoretical texts analysing this medium (to mention just the most frequently referred to names: Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes) artists are aware of photography’s limitations and formal problems. They don’t want to deal with those problems anymore, assuming that nothing more of importance can be said on the subject. Instead, they rediscover photography as a tool, not of artistic creation (as it was with the absorbtion of photographic elements into the realm of painting) but as a tool of the critical analysis of reality and historical mechanism. Photography of this sort is longer autonomous. Works of art such as those by Cindy Sherman, in spite of the fact that it served the purposes of analysing the query of gender and cultural identity, remain autonomous. So contrary to the American artist, Chris Meigh-Andrews does not equate the photograph with his artwork. On the one hand he utilizes the documentary power of photography as a historical source, on the other hand he is looking for something that is more than a simple photographic record; the historicity, continuity, and duration of the place/object. Because photography itself is not enough to capture this continuum, it must be connected with another medium having the ability to create duration. In the case of Meigh-Andrews’ installation, it is the video record. Questions concerning time expired between the moment of taking the photo and its viewing were always present, whereas now in the age of digital media when images are instantaneously viewed, the problem is no longer relevant. The work of Chris Meigh-Andrews is a metaphor for this change.

There is no more photography and no more video, having been replaced by installations that simultaneously show the past, present, and the moment of photographing and viewing. It gives the viewer a totally new realm of experience of something that cannot be captured, something illusive, impenetrable and real.

*From the original Polish version: Od narzedzia do dziela sztuki i z powrotem – czyli o roli fotografii we wspólczesnych instalacjach, published in “Biuletyn Fotograficzny”, March 2004. Translated by Aneta Krzemien and Stephen Barkley, 2004.